Reviews by Andrew Swafford and Michael O’Malley

Andrew’s Take:

In Cinematary’s coverage of TIFF 2023, I wrote about an avant-garde short film by Ja’Tovia Gary called Quiet as It’s Kept, which was primarily about blackness in relation to white supremacist beauty standards. Built primarily out of borrowed footage from all over the media landscape (from Toni Morrison interviews to YouTube makeup tutorials), the film was able to capture a sense of a larger cultural mosaic regarding its subject. This approach struck me as being part of an emerging genre of sample-based cinema, comparable to so-called plunderphonics music popularized by artists like DJ Shadow and The Avalanches. Other short films I’m aware of that would fit nicely in this category would be Love Is the Message, the Message is Death by Arthur Jafa, Polycephaly in D by Michael Robinson, and now BLKNWS: Terms and Conditions by Khalil Joseph – perhaps the first feature of the genre.

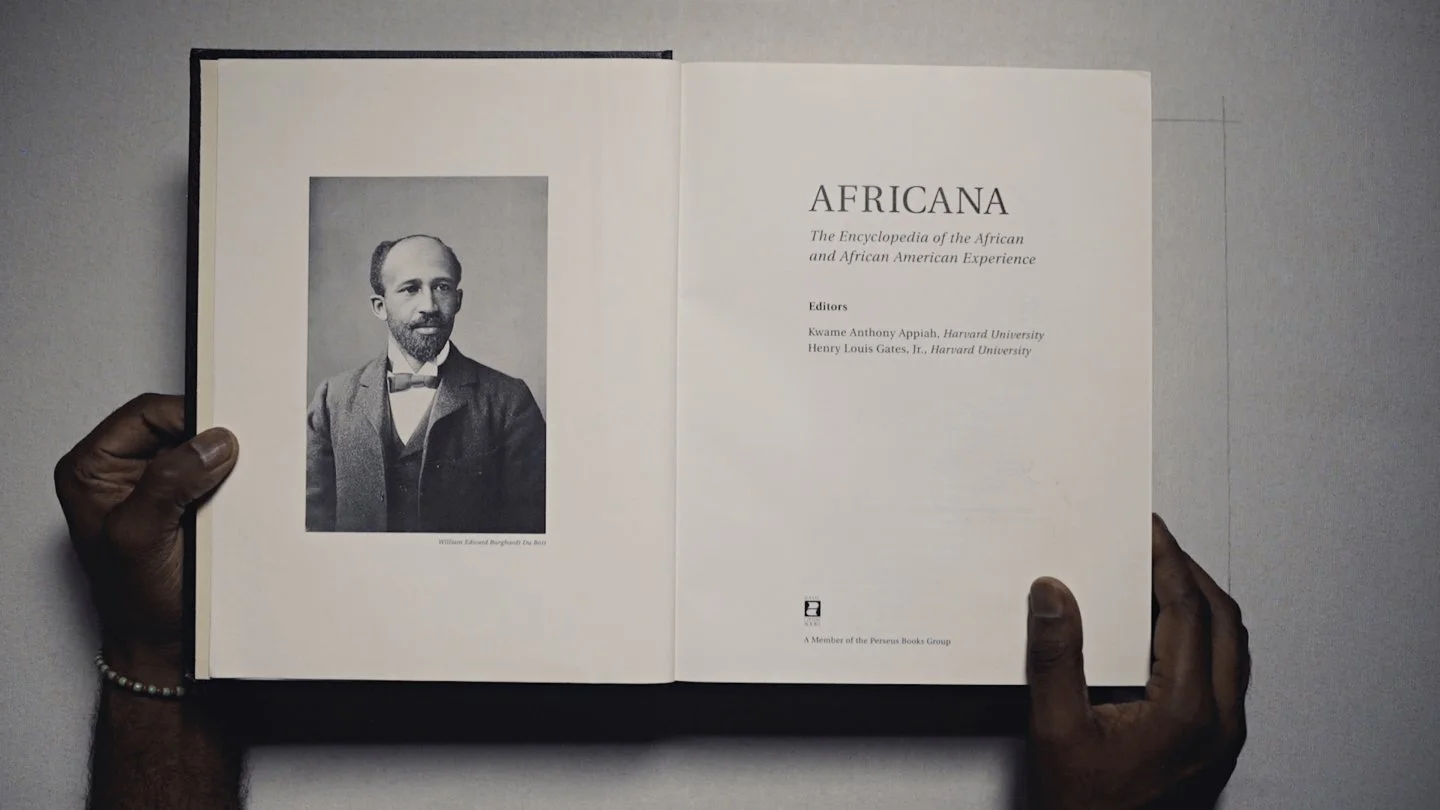

A director primarily known for his work on Beyoncé’s incredible Lemonade film, Khalil Joseph introduced BLKNWS by saying he structured the film like an album – but when the film starts, it announces itself as taking the form of an encyclopedia. A specific encyclopedia, in fact: Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African-American Experience, a compendium of knowledge about the African diaspora originally conceived of by W.E.B. DuBois. The prologue of BLKNWS approximates the experience of flipping through this encyclopedia, with video clips of all different aspect ratios and visual quality strobing past the audience at an electrifying pace – and set to an incredible beat, of course.

Perhaps because Joseph’s film is a feature rather than a short, it soon gravitates away from this hyperkinetic editing style into a different kind of fragmentation. The film has a number of modes it shifts back and forth between, one of which is a fictional news broadcast (BLKNWS) reporting on news from an imagined Afrocentric future (or parallel present) wherein the British monarchy is abolished, cultural artifacts stolen by colonial powers are returned to their countries of origin, and these same colonial powers have been paying reparations for decades. There’s a striking image in the film of W.E.B. DuBois standing in the middle of a hallway containing many doors, and to me, it seemed to suggest the idea of a variety of futures available to us from the present we find ourselves in.

What might those futures look like? One answer is provided by another one of the film’s modes – a comparatively conventional dialogue-based narrative following a journalist on a strange floating cruise ship tracing the original path of the transatlantic slave trade. The vessel is owned by a young black executive whose family were themselves implicated in the historical atrocity of trafficking slaves, perhaps implying something about the enduring corruption of that kind of blood money. The stretches of the film that take place on this ship are mysterious and languid, shot almost entirely in deep blues and browns and feeling more like a perpetual limbo than a journey to a specific narrative or thematic destination.

To me, these sections felt like they bring the otherwise thumping rhythm of the film to a dead stop, making me really feel the length of this nearly two-hour feature and wonder whether feature length is the right shape for this new wave of plunderphonics cinema. Perhaps if Joseph were to make the film the length of an album, the experience of watching it would feel entirely different.

In 2018, Joseph released a 30 minute film also called BLKNWS (sans the subtitle), so maybe that’s what I’m longing for. Regardless, I admire Joseph for refusing to be confined by conventional cinematic frameworks. At one point in the film, one of Joseph’s many borrowed video clips features the line “Style is a resistance to confine oneself,” and this type of shapeshifting, sample-based cinema has exactly that type of style in spades.

Michael’s Take:

Kahlil Joseph’s new feature film, BLKNWS: Terms & Conditions, feels unclassifiable at first blush. The film is something of a collage, assembled from a magpie’s nest of different video clips, both found and originally created, which makes it neither wholly documentary nor narrative, historical nor sci-fi, avant-garde nor traditional. A dazzling and dense piece of work, BLKNWS jumps from documentary interview footage to TikToks to sci-fi narrative to mockumentary to memoir to historical reenactment with a playful abandon of traditional divisions between media forms. One moment, you’re watching an SFX shot of an Afro-futurist submarine; the next, you’re treated to a clip of the iconic “Back at it again at Krispy Kreme” Vine; the next, you’re watching a scene from the 1962 film Vivre sa vie, re-subtitled to make it seem like Anna Karina is looking for a Wu-Tang Clan album at a Parisian record store. That’s just how things go in Kahlil Joseph’s culturally omnivorous vision.

As with any piece of art, it’s not as if this film is entirely without precedent. Godard’s post-’60s work comes to mind, as does Orson Welles’s F for Fake, or perhaps the perpetual eclectic montage of films like Man with a Movie Camera or the Qatsi trilogy (especially the second and third entries). The most immediate precedent is from Joseph himself, with his 2018 gallery piece BLKNWS. Like the 2018 film for which this new movie is a sequel of sorts, Terms & Conditions purports to be a broadcast from the titular “black news” broadcast, whose anchors present a series of clips with wry and occasionally uproarious commentary.

However, that description doesn’t really capture what’s so singular about the original 2018 BLKNWS or this new variation. In 2018’s BLKNWS, the accumulation of found media clips creates a sort of Pointalist portrait of black life, both mundane and exceptional, where the news broadcast framing device creates the sense that if news media actually chronicled the black experience, this is what it would look like. That element exists in Terms & Conditions as well. Prior to the TIFF screening of the feature, Kahlil Joseph explained that he crafted the film like an album, which was not surprising to hear; Joseph is probably most famous for his visual work with musical artists, having made music videos for acts such as Flying Lotus, FKA Twigs, and Kendrick Lamar, and almost certainly his most widely seen work to date is the companion film to Beyoncé’s Lemonade record, where he was the principal director. With that in mind, both the 2018 film and Terms & Conditions do resemble albums in general in the way that they flow almost in musical movements of rhyming collections of footage and Lemonade in particular in the way they attempt to encapsulate the broader black experience by intermingling an eclectic range of genres of black expression. In that sense, Joseph’s project between these two movies resembles the instantly iconic juke joint musical sequence in Ryan Coogler’s Sinners, where the whole history of African diasporic music inhabits a single shot. As in Coogler’s scene, there’s a celebratory, even utopian impulse to BLKNWS: a vision of black life in which the divisions of history, class, and high/low culture have dissolved into a single musical ecstasy—as one scholar interviewed in the film calls it, “the everyday anarchy of black life.”

However, anyone who’s seen Terms & Conditions knows that what I’ve just described is really only half of the movie, though, and to be honest, I’ve put off talking about the rest of the movie because I’m unsure what to make of it without further viewings. The media montage core of the 2018 film is merely one layer around which Joseph has wrapped two others, making Terms & Conditions considerably more expansive and wildly more complex than its 2018 forebear.

The first of these layers is an almost memoir-esque exploration of the book Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African-American Experience, a project begun by W. E. B. DuBois in 1909 and completed by Henry Louis Gates and Kwame Anthony Appiah in 1999. In the film, Joseph recounts how his late father gave this book to Joseph’s brother, Noah Davis, and how when Davis died of cancer, the book came into Joseph’s possession. This plunges Terms & Conditions into history, both universal and personal, in a way that far outstrips the scope of 2018’s BLKNWS. Interspersed with the “black news” threads are photos and pieces of writing, some cited with page numbers from Africana, others from Joseph’s own family archives picturing biographical images such as childhood homes and his father at the Million Man March, as well as historical recreations of an aging DuBois working on what would become Africana in his home in Ghana in the early 1960s.

The second layer Joseph adds to Terms & Conditions catapults the film in the opposition direction, into a far-flung future in which it seems that a political movement inspired by Marcus Garvey has achieved some measure of political success; as part of their program, the Neo-Garveyites now run a submarine that rockets between North America and West Africa in a cross between a cruise and an immersive museum exhibit, allowing black passengers to pass through something called the “Mid-Atlantic Resonance Field” that reconnects them with their ancestral lineage that was subjected to the Middle Passage. A major thread throughout the movie, woven among the “news” and the Africana segments, involves scenes of conversations that occur on that submarine between passengers (one of whom is a journalist writing an article about the submarine) and one of the curators of the experience.

Of course, Garvey and DuBois famously were at loggerheads regarding what the political goals of African Americans should be, which makes the inclusion of these two new layers turn the film into a dialectic between a DuBois past and a Garvey future, with the black news present staked between the two. I’ll confess that I don’t feel equipped to parse the nuances of that dialectic, especially having only seen this rich text of a film once, but what immediately comes to mind is another precedent that Joseph seems in conversation with: Lizzie Borden’s 1983 sci-fi film Born in Flames. Borden’s movie uses a mix of faux-news docufiction with interviews and real documentary footage to explore the aftermath of a future socialist revolution. The film is fairly cynical about the compromises and half-successes that would likely accompany a socialist revolution in the United States, but perhaps its most biting cynicism is the metatextual one of the prospect of socialist revolution in 1983 of all times, long after the radical hopes of the 1960s had been squashed by the reactionary forces that eventually culminated in the election of President Ronald Reagan.

Like Borden, Joseph juxtaposes the revolutionary spirit with a cold splash of struggle. In the 2018 film, this comes with the incorporation of footage of police brutality against black people, but to me, Terms & Conditions feels even more in the spirit of Born in Flames. While the original BLKNWS is very much a product of the Black Lives Matter era in terms of both its content (focusing on social media and the intersecting trauma of police violence) and essential optimism about the power of images to foment radical power, Terms & Conditions feels distinctly post-2020 and post-BLM retreat from the American political vanguard, in the same way that Born in Flames’s 1983 release feels post-New Left. There’s a distinct wistfulness in watching W. E. B. DuBois at the end of his life still wrestling with the same unresolved questions that inflect the 21st century black experience, and the cavernous distance between the struggle of the present moment and the imagined utopia of the Garveyite submarine makes those questions seem all the more mournful.

At the same time, it’s hard to call Terms & Conditions an elegy. The playfulness and energy that Joseph imbues the movie with when chronicling contemporary black life depicts a culture full of verve and creativity and, moreover, tenacity. The revolutionary potential Joseph found in 2018 still exists, if only in the stubborn hanging on, the insistence on finding beauty and play, and a spark that, even with every setback, simply continues to exist in defiance of a world bent on its extermination. DuBois may have died without the completion of Africana, but the work continued—and continues.