Review by Andrew Swafford

The Fence is a strange movie from Claire Denis – but only because of how straightforward it is. Renowned for her impressionistic and elliptical storytelling, Denis has famously challenged her audience to piece together fractured narratives and peer into the psyches of emotionally distant characters. Even in a film like High Life, which featured big name stars like Robert Pattinson and received an unprecedented marketing push from A24, was a shockingly confrontational and heady sci-fi film that forced its audience to stare into the abyss of monstrous brutality and cosmic indifference. Raised in French Colonial Africa, Denis is almost always concerned with the ways in which our world is built upon a foundation of normalized injustice – but I’ve never seen her explore that idea in a more ordinary way than she does in The Fence.

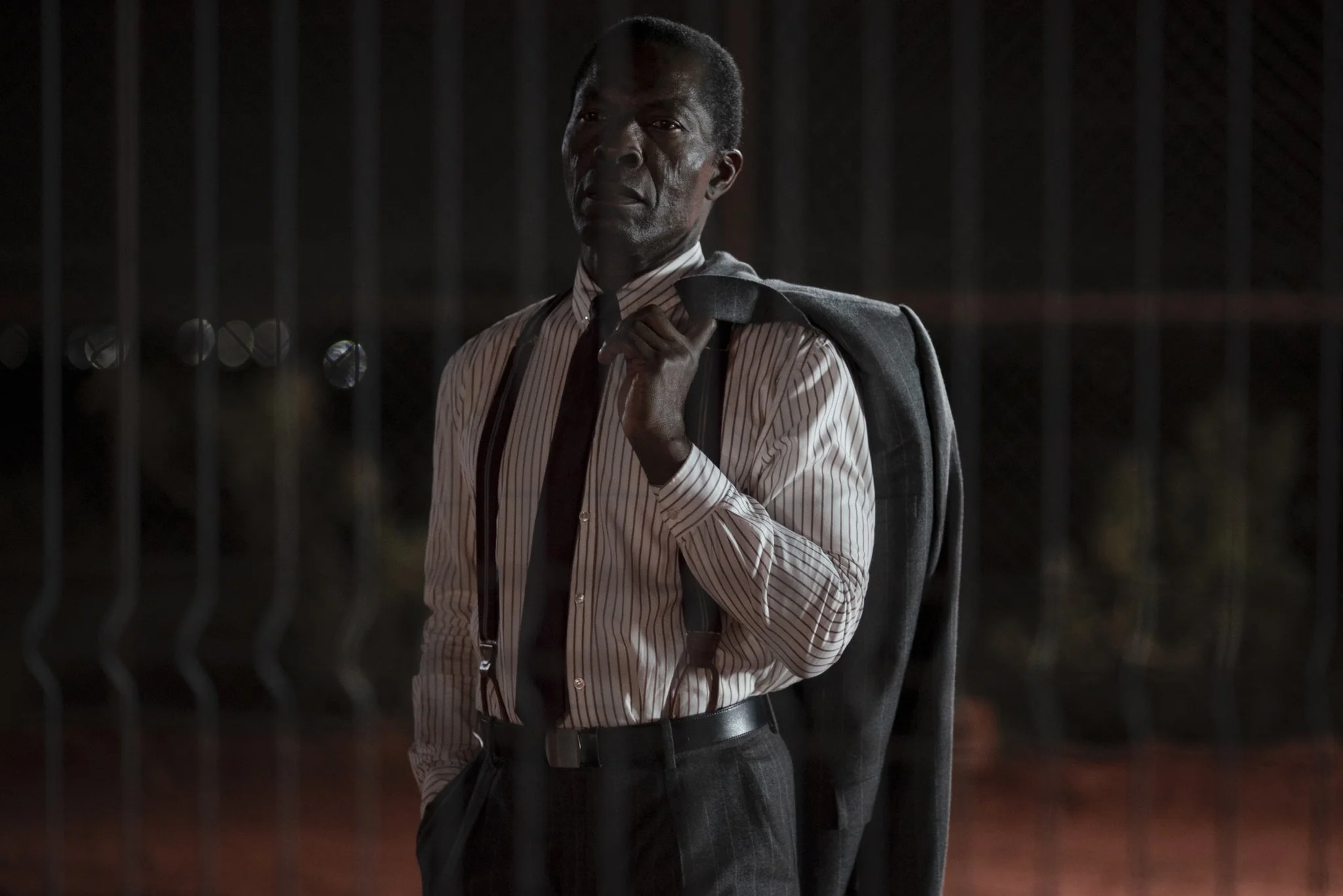

Her first film to be based on a play, The Fence is theatrical rather than cinematic in the most glaringly obvious ways: it takes place almost entirely on a single set, spans only a single night, and is constructed out of one circular dialogue scene after another. The story’s central conflict involves a white factory manager played by Matt Dillon, who has recently covered up the murder of one of his African employees at the hand of a white one. When Isaach De Bankolé shows up to collect the body, he is told to stay on one side of the titular fence while Dillon continually deflects and denies the story of the murder. On this same night, Dillon is also greeting his newly betrothed (and much younger) wife, who has been flown in from England like just another shipment he has placed an order for. The young bride’s presence makes the sustained tension of the nocturnal standoff that much more taut, until it of course explodes in violent and clearly allegorical fashion.

The best part of the film is obviously the performance of Isaach De Bankolé, who practically steams with repressed anger as he stands firm and indignant on his side of the fence, unwavering in his commitment to giving the recently deceased man – his brother – a dignified burial. Denis has always been a masterful photographer of the human face, and she’s well-practiced in capturing the weathered scowl of De Bankolé, who has starred in many of Denis’s best films. I wish the rest of the film shared De Bankolé’s ability to convey so much with so little, but it is unfortunately little more than a talky morality tale about the obvious villainies of postcolonial capitalism, racist violence, and patriarchal control. I admire Denis’s commitment to speaking her truth about these historical forces that continue to shape our world, but I wish that she had conveyed it in a way that was less easily summarized.